While we're on the subject of animated movies, can I just take a moment to declare that Ariel, youngest daughter of Triton, might be the worst sentient creature in the entire universe? Seriously, she doesn't appear to have a single decent characteristic about her.

She is, quite simply, a horrible creature.

She combines every negative stereotype about teenagers imaginable: she whines, she complains, she argues, she pouts. She is a pampered princess, daughter of the undisputed sovereign of Earth's entire ocean system (making him ruler of a territory that is many times more vast than the largest kingdoms in human history), and yet she still finds things to complain about. And whereas most teenagers issue complaints about problems that can, in theory, be solved rather easily (i.e., I never get to use the car, I never get to go to the mall, I never get to bring guns to school), Ariel decides that her big obstacle in life is that she's the wrong species.

Seriously, that's like your normal human teenager watching Curious George reruns and bitching that he's not going to be happy until he becomes a chimpanzee. It's ridiculous on every conceivable level.

But these aren't the worst aspects of her character. After making her deal with Ursula, Ariel heads off to the topside in order to woo Prince Eric, a moronic playboy sleaze who actually falls in love with a woman who can't speak and combs her hair at the dinner table with a fork.

Ariel's best friend is Flounder, a tropical fish. They talk together, swim together, plan together, cry together, share their dreams and hopes with one another - they are best friends. Flounder, like all fish in this universe, is a sentient being, an animal with thoughts and feelings, desires and dreams. He has emotions. He feels pain.

And yet Ariel does nothing to dissuade Eric from murdering and eating these beautiful creatures once she is focused on conning him into kissing her before her three days is up. The fact that Sebastian barely escapes with his life after being chased by a knife-wielding caricature of a French chef (good God, why is it okay to mock French people like this? No wonder they hate Americans...) apparently means nothing to her. At no point does she make any effort to explain to him that fish are... well, that fish are people, too. They are more than just food, they are rational animals, just like humans are.

Is it me, or is this something that she really needs to answer for?

Saturday, September 19, 2015

A Random Thought

Are the toys in the Toy Story universe immortal? We know that they can survive all sorts of crazy and dangerous pseudo-surgeries, switching heads and limbs and yet retain their sentience.

If the toys can die, then their human owners would never know, and would simply continue playing with them as though nothing happened. The other toys, however, would be aware that they are now forced to play with the rotting corpse of their deceased friend.

And that would be disgusting.

If the toys can die, then their human owners would never know, and would simply continue playing with them as though nothing happened. The other toys, however, would be aware that they are now forced to play with the rotting corpse of their deceased friend.

And that would be disgusting.

Tuesday, September 15, 2015

Miguelito, Revised

Miguelito

4:17 p.m.

Miguel Illescas walked down the crowded sidewalk that Thursday afternoon, nodding his head and waving his hands in acknowledgement of the various gifts that storekeepers, bartenders, and random passersby threw into his path.

He stooped down and picked up a rose from a bunch that littered the sidewalk in front of him without interrupting his gait, and confidently blew a kiss at a woman in a form-fitting purple dress who jumped up and down and shouted his name when she saw him. Gummi bears, candy bars, fresh fruit, flower petals, and ornate wreaths were all tossed by the grateful residents of the neighborhood as they crowded together to catch a glimpse of their savior and hero as he passed by.

It was, to be sure, almost more than an ordinary eight-year-old could handle.

Miguelito, however, was no ordinary eight-year-old, as his legions of adoring fans, followers, and hangers-on would gladly testify.

"Gracias, Miguelito," an old man said, holding out his hand, an abashed smile dominating his face. "Gracias por todo."

Miguelito took the man's weathered, wrinkled hand in his, looked deeply into the old man's dark eyes, and nodded. "We all do what we can," he said in typically humble fashion. Though his exploits were legendary, Miguelito had never felt comfortable with the praise and appreciation he received, and downplayed his contributions to the community's well-being every chance he could.

"Miguelito!" screamed a thirty-year-old woman as she dropped her husband's hand and ran over to embrace the child. "Miguelito, your autograph, please," she pleaded, but the boy simply shook his head and smiled.

"No autographs," he said simply, and the dejected woman returned to her husband, who did his best to console her.

As he walked farther on, towards the outskirts of his home neighborhood, the lines of his earnest and affectionate devotees began to thin out, until he found himself walking on deserted sidewalks.

Recognizing the sudden need for attentiveness and caution, Miguelito laced his thumbs through the shoulder straps of his tattered and worn Batman backpack and stole a quick glance over his right shoulder, scanning the empty streets for signs of troublemakers, recreants, or other delinquents.

Not seeing anything, Miguelito inhaled deeply, wiped the sweat from his brow with the back of his right hand, and continued on his way.

4:32 p.m.

Miguel ducked under the welcoming shade in front of local bodega, took off his backpack for a moment, and glanced down at his digital wristwatch. Satisfied at his progress, he strode back out into the sun, ditching the comfortable cover of the awning's shade. He still had a long way to go and a shrinking amount of time in which to get there.

As he walked, he noticed an older man sitting on a bench on a bus stop, having an animated conversation with nobody. He stopped a few feet from the man and watched as the one-sided discussion developed, the man becoming more agitated as he argued with somebody or something that Miguel couldn't see.

"Who are you talking to?" Miguel asked.

The man was startled by the boy's interruption, and jumped out of his seat. He turned around slowly and eyed Miguel with squinting eyes.

"Who I'm talkin'' to?" he asked, looking around. He shrugged. "He was jus' heah a minute ago. Mus've left. Ah, well, I in't like 'em anyway."

Miguel smiled, nodded, and continued to stare at the old man as though struggling to identify him.

"Hey, young man," the man said in hushed tones, motioning for Miguel to move closer. "I got sumpin' fo' you, sumpin' you ain't gon' wanna pass up."

Miguel pressed his eyebrows down in curiosity. "What is it?"

"Man, what I got's a million dolla idea, but I give it to ye fo' fi'e dolla."

"I don't have five dollars," Miguel explained, fishing around in his pockets.

"How much you got?" the old man asked, peering suspiciously at the boy.

Miguel shrugged. "I don't know. Maybe fifty cents."

"Fiddy cent?" the man asked, raising his voice in dismayed shock. "Fiddy cent? What kind o' fool gonna sell you a million dolla idea fo' fiddy cent? Man, I ain't gon' let go o' dis idea fo' nuttin' less dan one dolla."

Miguel shook his head. "I'm sorry, but I don't have a dollar." He brought out a handful of change from his pocket and started to count it. "I have... sixty-two cents. Is that enough?"

"Man, hand dat munny ovah," the man said with a disgusted look on his face. "Carefu' I don' run down to da police station and file a report on account o' how you rob me heah."

Miguel handed over his change and looked eagerly at the man. "So what's the million dollar idea?" he asked.

"Man, looka heah. You evah hear o' sumpin' called col' fusion?" he asked, raising his eyebrows at the import of his own words.

Miguel shook his head. "No. Is it some kind of new refrigerator? We need a new refrigerator at home."

The man nodded sagely. "Man, e'ryone need a new fridge now wit' dis damn heat. It's hotta den a camel ass out heah, I tell ya'. Heah," he said, handing over a tattered sheet of paper upon which he had made nearly-illegible scribbles. "You take care o' dat right theah, you hear me, boy? Dat right deah, in yo' hand, gonna change da worl' one o' dese days, an' you just stole it from me fo' sixty-two cent."

The man shook his head gruffly and began to walk away, muttering curses about the money he just forfeited in the transaction. Miguel glanced down at the paper, staring and squinting and trying to make sense of the letters, numbers, and strange symbols on the paper before folding it neatly up and putting it away in his pocket.

"Hey, Peddler," Miguelito called out, his voice imperious and commanding. "Stop right there. Not another step."

The old man stopped mid-stride, his shoulders high enough to cover his ears as he reflexively flinched at the use of his nom de guerre. He turned around slowly and faced the unassuming young man, his once cloudy eyes now bright and searching as he looked Miguelito up and down, curious about the unforeseen change in the child's manner and demeanor.

"Who you be?" the old man asked, squinting at Miguel.

Miguel smiled confidently. "I cannot express to you the depth of my heartbreak and disappointment, Peddler, at the fact that you don't recognize me," Miguel answered, advancing slowly towards the old man. "On these streets I am known by many names, but I prefer the one that strikes terror in the hearts of evildoers like yourself, Peddler. You know me as -"

"-Miguelito," he finished, his shoulders slumping and his gaze falling to the cracked grey concrete of the sidewalk beneath his feet.

"The very same," Miguel replied, nodding and continuing his methodical advance. "I am glad that we have met at long last, Peddler. I have heard of your misdeeds from afar, though, truth be told, I have always considered you to be more of a second-rate criminal and thus have you managed to avoid the burning sting of justice at my hands." He reached into his pocket and pulled out the folded-up sheet of paper he had just procured. He opened it slowly, unfolding it one section at a time until it had returned to its normal size. "Do you really expect me to believe that you have discovered the secret of cold fusion, Peddler? I scoff at the idea. Tell me, Peddler, where did you earn your advanced degree in chemistry?" Miguel crumpled the paper up and hurled it at the Peddler, throwing it with such force that it slammed into the old man's head and knocked him to the ground. He stood over the old man, who writhed on the ground in pain, clutching his bleeding forehead as he tried futilely to ease his headache. "Admit it, Peddler: this was just another ruse by which you planned to steal the hard-earned money of unsuspecting passers-by, isn't it? Isn't it?"

"Yes, Miguelito," the old man cried, sobbing and choking as blood began to drip down his sweaty forehead. "Yes, it's true. I never earned an advanced degree in chemistry. All I have is a bachelor's from Penn," he admitted howling in shame.

Miguelito shook his head in disgust. "That's barely even a real Ivy League school," he said, his hands resting on his hips. "You should be ashamed of yourself, Peddler. If I see you on these streets again, I promise that your days of selling off-brand merchandise and phony scientific breakthroughs to gullible civilians will be over. Now get up and pedal yourself out of my town, Peddler."

The old man nodded and continued crying as Miguelito walked away. He looked at his watch again - it was time to move on.

4:43 p.m.

As he continued on his way, Miguel again checked behind him, scanning the sidewalk carefully to make sure he wasn't being followed. While he suspected that he was being surveilled, there was nothing that he could do about it at the moment. He had to keep moving if he was going to make it in time.

Not seeing anything suspicious, the boy moved forward, again adjusting the straps on his Batman backpack so that it sat better on his shoulders. His hair was a damp mess from the humidity, and drops of dirty sweat continually dripped down into his eyes and onto his mouth, the salt blurring his vision and stinging a cut on his lower lip.

Unbidden, the thought of an orange popsicle entered into his mind, causing his tongue to swell and salivate with longing. Orange popsicles, in his opinion, were not only the best flavor of popsicle available - they were, in point of fact, the only popsicle worth eating.

Focus, he reprimanded himself, angry for the temporary lapse in concentration. He couldn’t afford the luxury of indulging a fantastical mirage of the sweet, life-saving goodness of an orange popsicle. This was serious business he was involved in, and giving in to childish habits could cost him his life if he wasn’t careful.

4:57 p.m.

Miguel ducked into a shaded alleyway and sought refuge behind a giant green dumpster that stood outside of the building nearest the street. He removed his backpack and went through its contents, making sure that he had everything that he might possibly need. Satisfied that he was prepared for the confrontation, he slid his arms back into the straps, wiped his sweaty palms on his red shorts, and returned to the sidewalk.

He stole into the doorway of a white brick building, closing the door silently behind him and pausing, listening to the thumping of his heart while he waited to ensure that nobody was following him.

Confident that he was alone, he locked the door behind him and entered the empty office. He tiptoed toward the receptionist’s desk, careful not to make any noise that might announce his presence.

There, he thought, inhaling deeply with anticipation. The target was present, staring intently at an open manila file folder.

5:02 p.m.

"Hola, Doctór," Miguel said, flashing a cocky smile at the older man.

The man turned around and stared at the diminutive child standing in the waiting room. He craned his neck to get a better view of the visitor, as everything below the boy's neck hidden behind the receptionist's counter. The man stared and stared, trying desperately to place the face that he saw before him, unable to make the connection.

Finally, after twenty seconds, recognition flashed in the man's mind, and he dropped the file folder from his hands and began backing away.

"No," he whispered, his face a mask of mortal terror. "Miguelito? No. No puede ser. It cannot be. You, you, you were supposed to have been taken care of."

"Ah, yes," Miguel said, vaulting himself over the counter and into el Doctor's office. "Your dastardly partner, el Dentista. It seems he wanted a crown for himself, but instead I gave him a good drilling. We won't be hearing from him again, Doctór: I gave him a fatal case of hurt fillings.

"But enough about the dear, departed Dentista. Let's talk about you, Doctór. There’s an old saying, how does it go? Ah, yes: an apple a day keeps the doctor away. I wonder if that is true," he said, removing a shiny red apple from his backpack.

"No," el Doctór whispered, trembling as he tried to open the locked window in his office, to no avail.

"There is no escape, Doctór," Miguel said, advancing slowly, tossing the apple back and forth between his two hands.

"No, por favor, Miguelito. Por favor. You will see - I will change my ways. I will devote my life to helping the sick and the weak, those who are not able to care for themselves. Yes, yes, yes. I will be a good Doctór, Miguelito."

"A good doctor? It’s a little late for that, you villain."

"No, Miguelito," the Doctor said, falling to his knees and clasping his hands tightly in front of his face. "Please, spare me the ravages of the Big Apple, Miguelito. Por favor, Miguelito, have pity on an old man."

“You know about the Big Apple?”

El Doctór nodded. “Yes. Yes,” he sobbed. “Everyone knows about the Big Apple.”

“Tell me about it,” Miguel said as he continued tossing it back and forth in front of the trembling Doctór. “Tell me about this Big Apple of which you speak.”

The old man sniffled and cleared his throat. “It’s… it’s… it’s a deadly weapon, Miguelito. A chemical bomb disguised as an ordinary apple. They say that you've spent years perfecting it, that it can kill in a matter of seconds and leave no trace.”

Miguel nodded. “That’s right. The Big Apple destroys everything that it comes into contact with. Nothing survives it. But enough about my marvelous weapons. I want you to confess, Doctór. I want you to acknowledge what you've done. I already got the whole story out of the Dentista before I strung him up by his floss, so don't think about lying to me."

El Doctór began sobbing hysterically, screaming and crying and rocking back and forth. "Okay, Miguelito. Okay. El Dentista and I made an unholy alliance. It's true. We worked together. Our plan was to poison the town's water supply by flooding it with... with... with sugar."

"Not just sugar, Doctór."

"No, no," he pled. "Don't make me say it."

"I want to hear the words from your mouth, you miscreant."

"Okay, Miguelito. Okay. Sugar and... and... and high fructose corn syrup." El Doctór wailed and sobbed as Miguel stood in front of him, shaking his head in judgmental disbelief.

"You were willing to go to any length just to ensure that your business was booming. You were even willing to poison innocent people just to make a few bucks. And to think that you took an oath to do no harm, Doctór. I gotta tell you, Doc: your prognosis is pretty bad."

"No," he whispered, staring at Miguel. "No. I want to live. I want to live. I'll never harm another patient again."

"You got that right, Doctór. But from what I can see, you have less than two minutes to live. Don't worry, though: I'm a professional."

Without another word, Miguel pulled back his arm, the deadly apple palmed tightly in his hand, and hurled it at el Doctór’s tear-stained face with all the force that his little arm could muster. El Doctór opened his mouth wide to scream, but before so much as a squeak escaped, the Big Apple smashed against his nose, spreading its vile, rabid flesh all over his face. Instantly el Doctór’s skin began to bubble and ooze, the acidic chemicals of the apple turning his face to a dripping mush.

5:14 p.m.

“Four out of five doctors know better than to mess with Miguelito,” the boy said as he turned to walk away. “I wonder what Mom made for dinner.”

4:17 p.m.

Miguel Illescas walked down the crowded sidewalk that Thursday afternoon, nodding his head and waving his hands in acknowledgement of the various gifts that storekeepers, bartenders, and random passersby threw into his path.

He stooped down and picked up a rose from a bunch that littered the sidewalk in front of him without interrupting his gait, and confidently blew a kiss at a woman in a form-fitting purple dress who jumped up and down and shouted his name when she saw him. Gummi bears, candy bars, fresh fruit, flower petals, and ornate wreaths were all tossed by the grateful residents of the neighborhood as they crowded together to catch a glimpse of their savior and hero as he passed by.

It was, to be sure, almost more than an ordinary eight-year-old could handle.

Miguelito, however, was no ordinary eight-year-old, as his legions of adoring fans, followers, and hangers-on would gladly testify.

"Gracias, Miguelito," an old man said, holding out his hand, an abashed smile dominating his face. "Gracias por todo."

Miguelito took the man's weathered, wrinkled hand in his, looked deeply into the old man's dark eyes, and nodded. "We all do what we can," he said in typically humble fashion. Though his exploits were legendary, Miguelito had never felt comfortable with the praise and appreciation he received, and downplayed his contributions to the community's well-being every chance he could.

"Miguelito!" screamed a thirty-year-old woman as she dropped her husband's hand and ran over to embrace the child. "Miguelito, your autograph, please," she pleaded, but the boy simply shook his head and smiled.

"No autographs," he said simply, and the dejected woman returned to her husband, who did his best to console her.

As he walked farther on, towards the outskirts of his home neighborhood, the lines of his earnest and affectionate devotees began to thin out, until he found himself walking on deserted sidewalks.

Recognizing the sudden need for attentiveness and caution, Miguelito laced his thumbs through the shoulder straps of his tattered and worn Batman backpack and stole a quick glance over his right shoulder, scanning the empty streets for signs of troublemakers, recreants, or other delinquents.

Not seeing anything, Miguelito inhaled deeply, wiped the sweat from his brow with the back of his right hand, and continued on his way.

4:32 p.m.

Miguel ducked under the welcoming shade in front of local bodega, took off his backpack for a moment, and glanced down at his digital wristwatch. Satisfied at his progress, he strode back out into the sun, ditching the comfortable cover of the awning's shade. He still had a long way to go and a shrinking amount of time in which to get there.

As he walked, he noticed an older man sitting on a bench on a bus stop, having an animated conversation with nobody. He stopped a few feet from the man and watched as the one-sided discussion developed, the man becoming more agitated as he argued with somebody or something that Miguel couldn't see.

"Who are you talking to?" Miguel asked.

The man was startled by the boy's interruption, and jumped out of his seat. He turned around slowly and eyed Miguel with squinting eyes.

"Who I'm talkin'' to?" he asked, looking around. He shrugged. "He was jus' heah a minute ago. Mus've left. Ah, well, I in't like 'em anyway."

Miguel smiled, nodded, and continued to stare at the old man as though struggling to identify him.

"Hey, young man," the man said in hushed tones, motioning for Miguel to move closer. "I got sumpin' fo' you, sumpin' you ain't gon' wanna pass up."

Miguel pressed his eyebrows down in curiosity. "What is it?"

"Man, what I got's a million dolla idea, but I give it to ye fo' fi'e dolla."

"I don't have five dollars," Miguel explained, fishing around in his pockets.

"How much you got?" the old man asked, peering suspiciously at the boy.

Miguel shrugged. "I don't know. Maybe fifty cents."

"Fiddy cent?" the man asked, raising his voice in dismayed shock. "Fiddy cent? What kind o' fool gonna sell you a million dolla idea fo' fiddy cent? Man, I ain't gon' let go o' dis idea fo' nuttin' less dan one dolla."

Miguel shook his head. "I'm sorry, but I don't have a dollar." He brought out a handful of change from his pocket and started to count it. "I have... sixty-two cents. Is that enough?"

"Man, hand dat munny ovah," the man said with a disgusted look on his face. "Carefu' I don' run down to da police station and file a report on account o' how you rob me heah."

Miguel handed over his change and looked eagerly at the man. "So what's the million dollar idea?" he asked.

"Man, looka heah. You evah hear o' sumpin' called col' fusion?" he asked, raising his eyebrows at the import of his own words.

Miguel shook his head. "No. Is it some kind of new refrigerator? We need a new refrigerator at home."

The man nodded sagely. "Man, e'ryone need a new fridge now wit' dis damn heat. It's hotta den a camel ass out heah, I tell ya'. Heah," he said, handing over a tattered sheet of paper upon which he had made nearly-illegible scribbles. "You take care o' dat right theah, you hear me, boy? Dat right deah, in yo' hand, gonna change da worl' one o' dese days, an' you just stole it from me fo' sixty-two cent."

The man shook his head gruffly and began to walk away, muttering curses about the money he just forfeited in the transaction. Miguel glanced down at the paper, staring and squinting and trying to make sense of the letters, numbers, and strange symbols on the paper before folding it neatly up and putting it away in his pocket.

"Hey, Peddler," Miguelito called out, his voice imperious and commanding. "Stop right there. Not another step."

The old man stopped mid-stride, his shoulders high enough to cover his ears as he reflexively flinched at the use of his nom de guerre. He turned around slowly and faced the unassuming young man, his once cloudy eyes now bright and searching as he looked Miguelito up and down, curious about the unforeseen change in the child's manner and demeanor.

"Who you be?" the old man asked, squinting at Miguel.

Miguel smiled confidently. "I cannot express to you the depth of my heartbreak and disappointment, Peddler, at the fact that you don't recognize me," Miguel answered, advancing slowly towards the old man. "On these streets I am known by many names, but I prefer the one that strikes terror in the hearts of evildoers like yourself, Peddler. You know me as -"

"-Miguelito," he finished, his shoulders slumping and his gaze falling to the cracked grey concrete of the sidewalk beneath his feet.

"The very same," Miguel replied, nodding and continuing his methodical advance. "I am glad that we have met at long last, Peddler. I have heard of your misdeeds from afar, though, truth be told, I have always considered you to be more of a second-rate criminal and thus have you managed to avoid the burning sting of justice at my hands." He reached into his pocket and pulled out the folded-up sheet of paper he had just procured. He opened it slowly, unfolding it one section at a time until it had returned to its normal size. "Do you really expect me to believe that you have discovered the secret of cold fusion, Peddler? I scoff at the idea. Tell me, Peddler, where did you earn your advanced degree in chemistry?" Miguel crumpled the paper up and hurled it at the Peddler, throwing it with such force that it slammed into the old man's head and knocked him to the ground. He stood over the old man, who writhed on the ground in pain, clutching his bleeding forehead as he tried futilely to ease his headache. "Admit it, Peddler: this was just another ruse by which you planned to steal the hard-earned money of unsuspecting passers-by, isn't it? Isn't it?"

"Yes, Miguelito," the old man cried, sobbing and choking as blood began to drip down his sweaty forehead. "Yes, it's true. I never earned an advanced degree in chemistry. All I have is a bachelor's from Penn," he admitted howling in shame.

Miguelito shook his head in disgust. "That's barely even a real Ivy League school," he said, his hands resting on his hips. "You should be ashamed of yourself, Peddler. If I see you on these streets again, I promise that your days of selling off-brand merchandise and phony scientific breakthroughs to gullible civilians will be over. Now get up and pedal yourself out of my town, Peddler."

The old man nodded and continued crying as Miguelito walked away. He looked at his watch again - it was time to move on.

4:43 p.m.

As he continued on his way, Miguel again checked behind him, scanning the sidewalk carefully to make sure he wasn't being followed. While he suspected that he was being surveilled, there was nothing that he could do about it at the moment. He had to keep moving if he was going to make it in time.

Not seeing anything suspicious, the boy moved forward, again adjusting the straps on his Batman backpack so that it sat better on his shoulders. His hair was a damp mess from the humidity, and drops of dirty sweat continually dripped down into his eyes and onto his mouth, the salt blurring his vision and stinging a cut on his lower lip.

Unbidden, the thought of an orange popsicle entered into his mind, causing his tongue to swell and salivate with longing. Orange popsicles, in his opinion, were not only the best flavor of popsicle available - they were, in point of fact, the only popsicle worth eating.

Focus, he reprimanded himself, angry for the temporary lapse in concentration. He couldn’t afford the luxury of indulging a fantastical mirage of the sweet, life-saving goodness of an orange popsicle. This was serious business he was involved in, and giving in to childish habits could cost him his life if he wasn’t careful.

4:57 p.m.

Miguel ducked into a shaded alleyway and sought refuge behind a giant green dumpster that stood outside of the building nearest the street. He removed his backpack and went through its contents, making sure that he had everything that he might possibly need. Satisfied that he was prepared for the confrontation, he slid his arms back into the straps, wiped his sweaty palms on his red shorts, and returned to the sidewalk.

He stole into the doorway of a white brick building, closing the door silently behind him and pausing, listening to the thumping of his heart while he waited to ensure that nobody was following him.

Confident that he was alone, he locked the door behind him and entered the empty office. He tiptoed toward the receptionist’s desk, careful not to make any noise that might announce his presence.

There, he thought, inhaling deeply with anticipation. The target was present, staring intently at an open manila file folder.

5:02 p.m.

"Hola, Doctór," Miguel said, flashing a cocky smile at the older man.

The man turned around and stared at the diminutive child standing in the waiting room. He craned his neck to get a better view of the visitor, as everything below the boy's neck hidden behind the receptionist's counter. The man stared and stared, trying desperately to place the face that he saw before him, unable to make the connection.

Finally, after twenty seconds, recognition flashed in the man's mind, and he dropped the file folder from his hands and began backing away.

"No," he whispered, his face a mask of mortal terror. "Miguelito? No. No puede ser. It cannot be. You, you, you were supposed to have been taken care of."

"Ah, yes," Miguel said, vaulting himself over the counter and into el Doctor's office. "Your dastardly partner, el Dentista. It seems he wanted a crown for himself, but instead I gave him a good drilling. We won't be hearing from him again, Doctór: I gave him a fatal case of hurt fillings.

"But enough about the dear, departed Dentista. Let's talk about you, Doctór. There’s an old saying, how does it go? Ah, yes: an apple a day keeps the doctor away. I wonder if that is true," he said, removing a shiny red apple from his backpack.

"No," el Doctór whispered, trembling as he tried to open the locked window in his office, to no avail.

"There is no escape, Doctór," Miguel said, advancing slowly, tossing the apple back and forth between his two hands.

"No, por favor, Miguelito. Por favor. You will see - I will change my ways. I will devote my life to helping the sick and the weak, those who are not able to care for themselves. Yes, yes, yes. I will be a good Doctór, Miguelito."

"A good doctor? It’s a little late for that, you villain."

"No, Miguelito," the Doctor said, falling to his knees and clasping his hands tightly in front of his face. "Please, spare me the ravages of the Big Apple, Miguelito. Por favor, Miguelito, have pity on an old man."

“You know about the Big Apple?”

El Doctór nodded. “Yes. Yes,” he sobbed. “Everyone knows about the Big Apple.”

“Tell me about it,” Miguel said as he continued tossing it back and forth in front of the trembling Doctór. “Tell me about this Big Apple of which you speak.”

The old man sniffled and cleared his throat. “It’s… it’s… it’s a deadly weapon, Miguelito. A chemical bomb disguised as an ordinary apple. They say that you've spent years perfecting it, that it can kill in a matter of seconds and leave no trace.”

Miguel nodded. “That’s right. The Big Apple destroys everything that it comes into contact with. Nothing survives it. But enough about my marvelous weapons. I want you to confess, Doctór. I want you to acknowledge what you've done. I already got the whole story out of the Dentista before I strung him up by his floss, so don't think about lying to me."

El Doctór began sobbing hysterically, screaming and crying and rocking back and forth. "Okay, Miguelito. Okay. El Dentista and I made an unholy alliance. It's true. We worked together. Our plan was to poison the town's water supply by flooding it with... with... with sugar."

"Not just sugar, Doctór."

"No, no," he pled. "Don't make me say it."

"I want to hear the words from your mouth, you miscreant."

"Okay, Miguelito. Okay. Sugar and... and... and high fructose corn syrup." El Doctór wailed and sobbed as Miguel stood in front of him, shaking his head in judgmental disbelief.

"You were willing to go to any length just to ensure that your business was booming. You were even willing to poison innocent people just to make a few bucks. And to think that you took an oath to do no harm, Doctór. I gotta tell you, Doc: your prognosis is pretty bad."

"No," he whispered, staring at Miguel. "No. I want to live. I want to live. I'll never harm another patient again."

"You got that right, Doctór. But from what I can see, you have less than two minutes to live. Don't worry, though: I'm a professional."

Without another word, Miguel pulled back his arm, the deadly apple palmed tightly in his hand, and hurled it at el Doctór’s tear-stained face with all the force that his little arm could muster. El Doctór opened his mouth wide to scream, but before so much as a squeak escaped, the Big Apple smashed against his nose, spreading its vile, rabid flesh all over his face. Instantly el Doctór’s skin began to bubble and ooze, the acidic chemicals of the apple turning his face to a dripping mush.

5:14 p.m.

“Four out of five doctors know better than to mess with Miguelito,” the boy said as he turned to walk away. “I wonder what Mom made for dinner.”

Friday, September 11, 2015

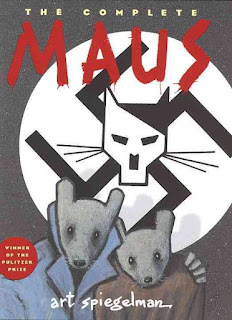

Quiet as a Maus

The other day, while rummaging through more boxes in the upstairs closet, I rediscovered a copy of two old graphic novels that I had nearly forgotten about: Maus and Maus II. Written by Art Spiegelman and first published in 1980, when I was but two years old, they tell the true story of Spiegelman's father and his terrible journey as a Polish Jew during the anti-Jewish pogrom carried out during the Second World War.

It is a brilliant, heart-wrenching look inside the scarred heart and psyche of a man who was subjected to the darkest side of the human condition and somehow lived to tell his story. In his expert rendering, Spiegelman draws Europe's Jews as mice, forced to scurry about underfoot and scrounge food and subsistence wherever possible, always in danger of being pounced upon by Nazi cats. The Poles are pigs, the French are (predictably) frogs, and Spiegelman himself is depicted as a human wearing a cheap mouse mask.

If you haven't read the books, please take the time to do so. It is important to learn about the depths of human depravity, but also to bask in the reflected glow of the triumph of human decency as embodied by Spiegelman's troubled father.

It is a brilliant, heart-wrenching look inside the scarred heart and psyche of a man who was subjected to the darkest side of the human condition and somehow lived to tell his story. In his expert rendering, Spiegelman draws Europe's Jews as mice, forced to scurry about underfoot and scrounge food and subsistence wherever possible, always in danger of being pounced upon by Nazi cats. The Poles are pigs, the French are (predictably) frogs, and Spiegelman himself is depicted as a human wearing a cheap mouse mask.

If you haven't read the books, please take the time to do so. It is important to learn about the depths of human depravity, but also to bask in the reflected glow of the triumph of human decency as embodied by Spiegelman's troubled father.

Wednesday, September 9, 2015

At the Intersection of Lord Ganesh and Nookie

My father-in-law is a well-read and widely-traveled man.

An Indian citizen by birth, Vikram was actually born in Thailand just after India finally achieved independence from the collapsing British Empire in 1947. His father, an engineer by training, worked in various positions for the United Nations throughout South and Southeast Asia, and at the time of the birth of his first child was overseeing a project to rebuild a Bangkok that had been decimated by the Second World War.

Fast-forward twenty-one years and Vikram had moved from rural Gujarat, the state in western India that his family has called home for generations, to California, where he had begun classes at UC Hayward in pursuit of his MBA.

Not long after he graduated from college, he met and married his wife, Smita, also a Gujarati. They settled down in Cherry Hill, New Jersey, an affluent suburb of Philadelphia, and raised three children, two of whom spent much of their childhoods at an exclusive Indian boarding school and one of them, my future wife, who was allowed to experience the ups and downs of life as a resident of New Jersey.

After their three kids grew up, moved on, and started lives and families of their own, Vikram fulfilled a life-long dream of his by returning to Gujarat in order to manage a charitable organization that his grandfather had founded more than fifty years before. Smita, considerably less excited to leave the comforts of life to which she had grown accustomed during thirty years in America, remained behind for several years before eventually surrendering and joining her husband.

A year or so after my wife and I were married, we packed our bags and embarked upon a twenty-hour airplane ride to join her father on his Gujarati estate.

Life in India during the unbearably humid monsoon months can often devolve into a contest among adults and children to see who can sit as still as possible in order to avoid generating any more sweat on his body. One must consider a number of factors before committing to any physical movement, taking into account the immediate necessity of moving, subtracting the disgusting inconvenience of adding to the layer of sticky, salty sweat that has congealed onto one’s body in the form of a biological gelatin, and arriving at the final determination of whether or not to stand up.

When it is 110º F and 100% humidity, peeing oneself while sitting motionless on the couch is not always an irrational decision.

Of course, going for a walk outside in such weather conditions is not an option, so when one makes a decision to leave the comfort of a partially-air-conditioned home, what one is, in fact, agreeing to is making a mad dash from the front door of the house into the thick wall of heat that is always waiting just outside of the house to suffocate you, sprinting across the slowly melting driveway and diving headfirst into the scorched seats of the waiting car.

If you've never experienced the sheer terror of a car trip in India, I envy you. Though I estimate that I have spent a cumulative total of less than one hundred hours in various automotive contraptions within the geographically-defined borders of India, I blame that small amount of time for my early-onset baldness, an anxiety disorder, and a stuttering problem that has strangely persisted for over ten years now.

Indian roads, whether the well-paved variety in New Delhi or the dust-and-gravel sort that provide access to the hidden gems of the Indian countryside, are utilized equally by all Indian animals, human and otherwise. These roads are thus home to packs of mangy dogs who gather to discuss the impending monsoon rains, camels who scoff at the poorly-evolved creatures who need regular drinks of water in order to survive, and cows, who enjoy simply sitting in the middle of traffic and flipping their tails at passersby in boastful flaunting of their revered status among a large portion of the population.

And there is nothing more infuriating than having to swerve at breakneck speeds around a cow with an inflated opinion of itself.

One morning, just after breakfast, my father-in-law pushes himself away from the table, rubs his stomach, and hums an unidentifiable tune for a minute.

"How 'bout we get in de car and drive to Baroda?" he asks. Baroda is a large city about thirty miles south of the bustling town where we are staying, which is a long way of saying that it's a place where we have a good chance of finding Doritos and Diet Coke.

Having absolutely nothing better to do with our morning, my wife and I agree to the invitation, and within minutes we are on the road and headed to Baroda.

My father-in-law waves off the driver, shunning the services for which the man is paid and opting instead to take our lives into his hands. We pile into the car and peel out of the driveway and onto the mostly-paved road.

"Muttyu," he says, puncturing the air with precise jabs of his left hand, "if you are going to be Indian, man, den you must learn about our mitts."

"Your mitts?"

"Yeah, man, our mitts. Dey our important, our mitts. Dey tell us stories about where we come from, man. About who we are as Indians, as Hindustanis."

"Your mitts tell you this?"

"Prerna!" he yells to my wife in the backseat. "Tell him, man. Our mitts our important."

"Myths," she corrects.

"Dat's what I said, man. Mitts. Okay, Muutyu. So, our mitts our important to us, yeah?"

I nod. "Definitely."

"Okay. So, what do you know about Indian gods, man?"

I shrug. "Not much," I admit. "I mean, I've read a bit about-"

He grimaces and waves me off impatiently. "Never mind your reading. You can't learn anyting from books, man. To learn about someting, you must go dere and experience it. To learn about a country's mitts, you must go to de country. You understand, man?"

I nod and shrug. "Sure," I say, ignoring that little urge inside of me to point out that he just dismissed the entire concept of learning by reading.

No matter.

"Good, man. Now, de important ting about India is that we have lots of gods, man. We have so many gods dat we don't even know who they are, man. Millions of gods. But dere is one god who is the best of dem all. Do you know who de best god is?"

I shake my head. "I have no idea."

He again waves dismissively at me, though this time the wave doesn't seem connected to the conversation I think we're having and seems to be nothing more than an impatient reminder that I have nothing substantive to contribute to this conversation, no matter how long it continues for.

"Of course you have no idea, man. How can you have ideas about Indian gods, man? You're not Indian. But don't worry. We will change dat. By de time I am tru wit you, Muttyu, you'll be demanding discounts from your own parents, man. Den you will be an Indian, man.

"Okay, so de best god is Ganesh. No question about it. You ask anyone and dey tell you, man: Ganesh is de best god."

"What are you talking about, Dad?" my wife interjects from the back seat. "That's not true."

"Not true what?" he demands, literally turning around in his seat while driving and staring at her.

I feel like I have to repeat myself in order to make clear what is happening at this moment. We are in the middle of monsoon season in India, which means not only are the roads covered in a semi-permanent coating of moisture, but that it is 100 degrees with 100% humidity, so the windshield is so fogged-up that we can barely make out any shapes in front of us. Drivers in India generally use their horn instead of their brakes, so one avoids a collision with other drivers not by slowing down but by honking on one's horn, flashing one's hazard lights, and swerving maniacally into oncoming traffic.

In a country of 1.2 billion people, who cares about road fatalities?

While driving in these unforgiving conditions, my father-in-law has just flipped his middle finger at both fate and common sense and has now turned around so that he is facing his daughter in the backseat, and proceeds to engage her in an argument.

"Prerna!" he yells. "What are you talking about, man? You know noting about Indian gods, man. You grew up in New Jersey, man. Your parents didn't teach you anyting about dese tings, man."

"You're one-half of my parents, Dad," my wife points out.

He nods. "I know, and I had no patience for you, so I didn't teach you anyting. You're de worst Indian, man. Look, you even went and married a gora, man." A gora is a white person. He turns to look at me. "No offense intended, Muttyu. You're a better Indian dan she is, man."

"No offense taken."

Satisfied that he has prevailed in the argument, he turns back around and swerves around a rickety red bus that is so overcrowded that people are literally sitting on the roof of the bus as it barrels down the highway at 70 miles per hour.

"Now, where was I? Yes. Ganesh is the best god. Don't argue wit me, Prerna. You don't know anyting, man. Anyway, do you know de story of how Ganesh got his head, man?"

I shrug. "Uh, he wasn't born with it?"

He looks at me, his face contorted in a painful mixture of disappointment and annoyance. "What are you talking, man? How is he gonna be born wit an elephant head, man? Does dat make sense to you, man? He gets born wit an elephant head, you tink his moder's gonna be happy wit him, man? What do you know about vaginas, man, if you tink a boy can be born wit an elephant head?"

"Oh my god, Dad," my wife whines from the back. "Did you just ask him about vaginas?"

"I sure did, man," he replies. "How can a husband not know more about vaginas, man? Muttyu, a woman's vagina doesn't have de strengt or the elasticity to be able to squeeze an elephant head tru it, man."

I shake my head from side to side in embarrassment. "That's good to know," I say. "I could have just skipped biology class and come straight to you."

"Man, no more talking, okay?"

I nod silently.

"Good. Now, Ganesh wasn't born wit an elephant head, man. He was just a boy. His parents were Shiva and Parvati. Do you know dem?"

I shake my head silently, afraid now to speak, visions of elastic vaginas floating around in my head.

"Dey're gods, man. Big gods, like head honcho gods. Shiva is like de Godfadder, man."

"Did you just compare Shiva to Don Corleone?" my wife shouts from the back seat.

My father-in-law nods defiantly. "I did, man. What's wrong with dat? It’s a compliment, man. Corleone got his own books and movies, man. Shiva is de Don, man. He makes offers you can't refuse. He takes de gun and leaves de cannoli. You get it, right Muttyu?"

I nod. I would gladly follow a god who reminds the masses of Don Corleone, especially if he was shadowed by Luca Brazi.

"Okay, so Shiva and Parvati get togeder one night for some nookie, and wham, bam, boom, Ganesh appears."

"Nookie?" my wife interjects. "What is wrong with you, Dad?"

He waves her off and continues. "Nookie, man. Even gods need it. Anyway, de nookie happens, as nookie does, and Ganesh is born. Now Shiva, he's an important god, man. He has tings to do. He likes to hunt."

"Why does a god like to hunt?" I ask.

"Man, who knows why gods do de tings dey do?" he asks rhetorically. Before continuing with his lesson on the pastimes of Hindu deities, he opens his car door - like, fully opens his car door as we're zooming down the pot-holed road at nearly 80 miles an hour - drops, his head, and spits out of wad of paan.

Now, paan, for those of you who are not acquainted with it, is a form of Indian chewing tobacco that utilizes betel nut, a natural stimulant. Men all over India can be seen with teeth that are stained blood-red, and these same men are responsible for the ubiquitous dots of red spittle that stain and discolor Indian sidewalks and roads.

"Dad!" my wife screams from the back seat. "What are you doing? Get back in the car!"

He wipes his mouth with the back of his hand, rolls his eyes, and hisses at her. Hisses - really hisses - like an enraged cat. "You Americans, you're all so worried about everyting. What could happen? We are talking about de gods, man. Dey won't let us die right now, not when we're talking about dem. De gods have big egos, man.

"So, Shiva, man, the Godfadder of de mob of gods, he likes to hunt, see? So one day he goes out hunting. Now his wife, man, Parvati, she's an Indian god, too, man, but she's a woman god, and all Indian women are de same, man. Dey have to be clean and pretty all de time, man. So Parvati spends all of her time in de battub, man, using saffron soap to keep her skin clean, man. And she doesn't want to be boddered, man, so she hires a bunch of armed soldiers to guard de entrance to her castle so that nobody can bodder her when she's baiding.

"But den Shiva finishes wit his hunting, man, and he hasn't seen Parvati in a long, long time, and he's a man, Shiva is, so he has needs, man. Do you know what I mean, Muttyu?" he says as he shakes his head back and forth playfully, his lips curling into a mischievous smile. "Shiva wants some nookie, man, and he wants it now."

"Dad, Shiva did not want nookie," my wife insists. "You can't say that a god wanted nookie."

"What you want I say, Prerna?" he demands, annoyed at my wife's constant interrupting. "What, he wanted carnal knowledge of his wife? Is dat better for your American ears? Pshh," he spits, flinging his hand impatiently through the air. "Anyway, Shiva wanted some nookie, man, so he went home to his castle where Parvati was baiding, but soldiers were guarding de doors and dey wouldn't let him in.

"So Shiva looks at dem and says, 'Are you guys serious? Do you know who I am, man? I'm Shiva, de Don Corleone of this whole planet, man. I want to see my wife so I can have some nookie, man.'”

Mid-sentence, without losing a beat, he swerves around two lazy camels resting in the middle of the road. As he passes them, he rolls down his window, spits out a wad of paan, and yells, “Stupid bloody camels!” with a fierceness that makes me question whether he believes they can understand him.

"But dey wouldn't let him in, so he beat de shit out of dem, man. He killed dem, he murdered dem, and den he went inside and got his nookie. But Parvati, man, she was pished.”

“Pished?” I ask, not recognizing this new word.

“Yeah, man, pished. Prerna, what is pished?”

“Pissed, Dad.”

“Dat’s what I said, man. Pished. You got it, Muutyu?”

“I got it. Pished.”

“Dat’s right, man. Pished off. She didn’t want to be boddered while she was baiding, man, so she sends her son Ganesh to guard de door to de castle after Shiva leaves to hunt some more. Now, remember: Ganesh is a god, man. He’s not some lackwit soldier, man. Ganesh is like de Terminator, man.”

“Dad, how is Ganesh like the Terminator?” my wife asks.

“Man,” he says, looking at me with pity in his eyes. “Do you have to listen to dis all de time, man? You couldn’t find a better wife dan her, man? She just won’t let us talk, will she, man?”

I smile. “She’s not that bad.”

“Not dat bad, man?” he says, shaking his head back and forth. “Not dat bad. Congratulations, Vikram. Your daughter is not dat bad. Fadder of de year, man. Anyway, Ganesh de Terminator is now standing guard at de castle door when Shiva comes back from his next hunting trip, man. But Shiva hasn’t been around much during Ganesh’s life, so he doesn’t recognize him, man.

“He says, ‘Outta my way, you ugly loser, man,’ and tries to push past Ganesh, but Ganesh is too strong, man. He doesn’t move. So Shiva steps back, and now he’s angry. Shiva says, ‘Man, you get outta my way before I do a flying elbow smash and take your ugly head off of your shoulders, man.’

“But Ganesh won’t move. Parvati has told him to stand guard, and he’s a good Indian boy and he listens to his modder, and he’s not going to let anyone into de castle. So Shiva says, ‘Alright, man. To hell wit dis shit, man.’”

“Shiva didn’t say that, Dad,” my wife complains.

“How do you know what Shiva said, man? Gods can say what dey want, man. He says, ‘To hell wit dis shit, man,’ and he takes off Ganesh’s head wit his bare hands and trows it into de woods behind him. He walks upstairs, sees Parvati in de battub, and says, ‘Woman, I want some nookie.’

“But Parvati, man, she is pished. ‘Where is my son?’ she screams. ‘What did you do to my son?’ And Shiva now knows what happened and he says, ‘Oh, shit, man,’ because he knows dat Ganesh is deir son. And he says, ‘Look, woman, I know you’re upset and all, but let’s do de nookie dance first, and den we can tink about your son.’

“Of course dis doesn’t work, man, and Parvati says, ‘Man, you better fix dis if you ever want nookie again, man.’ So Shiva says, ‘Fine, man,’ and he sends his little toady out into de forest and says, ‘Man, just get me the head of de first animal you see, man.’”

In front of us is a truck that is overloaded with bales of hay. My father-in-law honks once, twice, three times, but the bus isn’t moving out of our way, so he presses down on his horn and holds it there as he swerves onto the grass on the right shoulder and passes the truck.

“Dis stupid guy, man. Eider learn to drive or get off of my road, man.

“So, anyway, dis guy, Shiva’s toady boy, goes out, sees an elephant, and wham, chops off his head. He brings de elephant head back to de castle, and Shiva puts it on Ganesh’s shoulders, and den he brings de boy into Parvati’s room to show her dat he fixed everyting, man.”

“Wait, what?” I ask. “He beheaded his son, then tried to fix it by attaching an elephant’s head in place of the human head that he cut off?”

“Yeah, man. He didn’t have time to find a better one. Didn’t I tell you dat he was horny, man? He needed nookie. So Parvati sees her boy wit an elephant head, and she says, ‘Okay, fine. Get your nookie den get out of my castle, man.

“And dat’s de story of Ganesh, man.”

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)